There's a knowledge gap between owning, working with farm families, and deploying capital for savvy investors, says Crescero founder and CEO

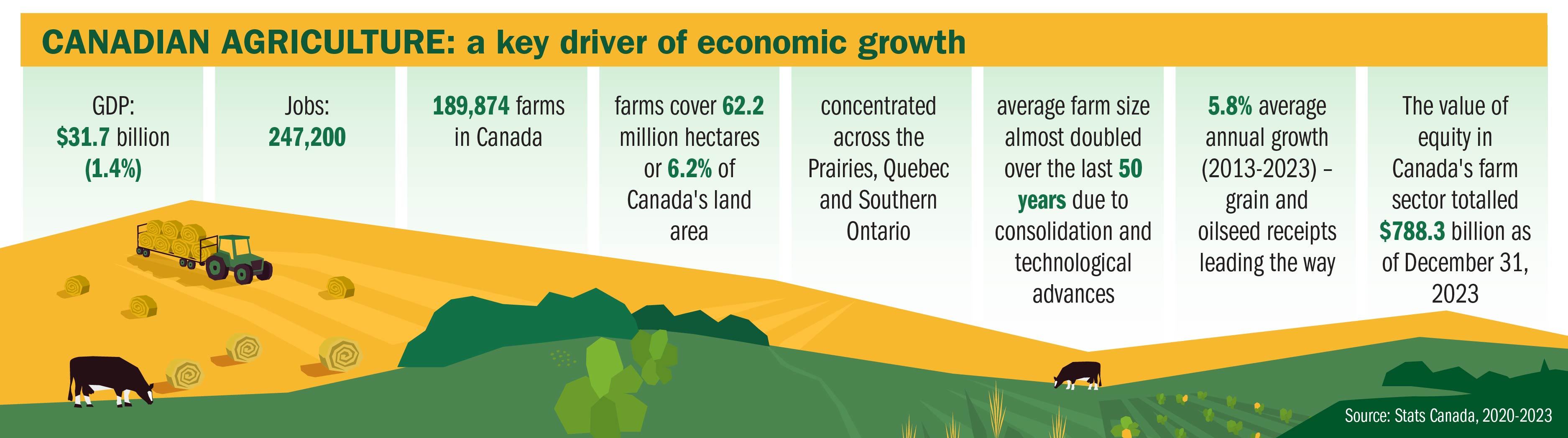

Amid the “buy Canadian” sentiment making waves across the country, Kent Willmore believes institutional investors who want long-term, stable returns may be missing a promising asset class in their portfolio: Canadian farmland.

Despite its low volatility, strong historical performance, and increasing strategic importance, Canadian farmland remains largely underrepresented in institutional portfolios. The CEO and founder of Crescero Natural Capital, formerly AGinvest, was quick to highlight this sentiment needs to change.

“It's a great diversification tool, with really low volatility, very stable returns over many decades. It’s tangible, and you can stand on it,” said Willmore. “It’s a really unique asset class that way.”

“There's so many things about investing in this asset. It's not only a feel-good story but it actually has a very good track record of returns. It’s confusing to me why institutional investors haven't partaken more in this,” added Willmore.

Willmore, who’s also a farmer himself, explained part of the challenge in attracting institutional capital is that farmland, unlike traditional real estate, hasn’t been fully institutionalized yet.

“If we go back to the 90s and think about how institutions started involving themselves in multi-family homes, condos, office towers, all of those things were owned by individuals and small businesses,” he said. “Farmland is the last trillion dollar asset class that has yet to be institutionalized.”

Yet, institutional investors have been slow to participate. Willmore cites a few reasons for this, starting with a lack of access, noting Crescero is one of the few asset managers investing in farmland in the whole country. Another challenge is the fragmented nature of farmland, particularly in Ontario, making it difficult to deploy capital efficiently.

But perhaps the biggest barrier Willmore acknowledged is “a lack of education in the space.”

“Institutional investors are very savvy, they’re very educated and intelligent. I just think there’s a gap between owning, managing, working with farm families, and deploying capital,” said Willmore.

That becomes particularly apparent when looking at farmland ownership. He estimated that institutional investors hold less than 1 per cent of Canada’s $1 trillion in farmland, with the vast majority owned by farm families.

However, he emphasized that landscape is set to shift dramatically with most farm families facing a significant succession issue over the next decade.

“It’s our estimation that between 50 and 75 per cent of that has to change hands in the next 10 years,” he noted.

For institutional investors, that represents a $500 billion to $750 billion opportunity but also a pressing need to engage with farm families in a way that aligns with long-term sustainability and food security.

“We need institutional investors to be partaking in this and to be working with farm families and to help the future food security of this country and our planet,” he said.

He emphasized it’s more than just explaining the financial case; it’s also about navigating the political and social dynamics of farmland ownership.

“If you don’t handle farm families correctly...you can’t deploy capital in a way that’s reckless to the farm side of the equation,” he said, emphasizing farm families “are the closest thing to a politician’s direct phone number.”

Farmland’s appeal is also being shaped by climate change, but not in the way some might expect. Canada’s farmland is seeing longer growing seasons and increased rainfall, as Willmore emphasized the country is “actually a net beneficiary of climate change.”

“In Ontario, especially in many other parts of the southern regions of Canada, we’re getting warmer and wetter, and that’s only good for farmland and soil,” he added.

Water access in Canada is another advantage. While some of the largest institutional farmland investments have been made in regions like California, the US Midwest, and Australia, water scarcity for these areas are a growing concern.

By comparison, Ontario and much of eastern Canada benefit from consistent rainfall, reducing the need for irrigation. Willmore sees this as a fundamental reason why capital should be flowing into Canadian farmland, rather than to regions struggling with water security.

“You can have the best soil and the best farmland in the world but if you don’t have water, you don’t have anything,” he said. “If you don’t water those seeds, nothing grows.”

Sustainability is also a critical piece of the investment equation, though Willmore asserted the concept of sustainability doesn’t go far enough.

“Sustainability just means maintain,” he said. “Our goal is to make it regenerative.”

For Willmore, that means actively improving soil health, increasing productivity, and ensuring farmland remains viable for generations.

The stakes are notably high for farmland, Willmore noted because each year, the planet gains 40 to 60 million more people while losing 20 to 30 million acres of farmland.

“That is not sustainable at all,” he said. “But that does speak to the reason to own farmland.”

Ultimately, the question isn’t whether Canadian farmland is a compelling opportunity. Willmore emphasized it’s why more investors haven’t moved into the space already.

“It's not just an investment, it's a necessity. How much do you want to be apart of this opportunity? Because it's a fantastic opportunity when we look ahead,” said Willmore, adding Crescero derived from the Latin verb crescere, which means “to grow.” And that’s what they want to be doing as a company.

“We want to be growing value for our investors and we want to be growing opportunities for our farm families. We want to be growing sustainable solutions for future agriculture and for global food security,” Willmore said.